News & Trends

Doughnut Economics

A Somewhat Different Economic Theory

The “growth equals prosperity” equation has been used as a universally valid formula for about six decades. This way of thinking undoubtedly gave us our current standard of living. Yet even today, our economic system presupposes growth as a fixed variable. But isn’t it time to focus on human well-being?

Humans consume more resources than the Earth can regenerate, and social inequality is getting noticeably worse. Is the path of perpetual growth in reality a one-way street and does it possibly lead to a dead end? Or is the eternal “higher, faster, further” actually bringing our planet completely to its knees?

Growth and Prosperity – an Inseparable Pair?

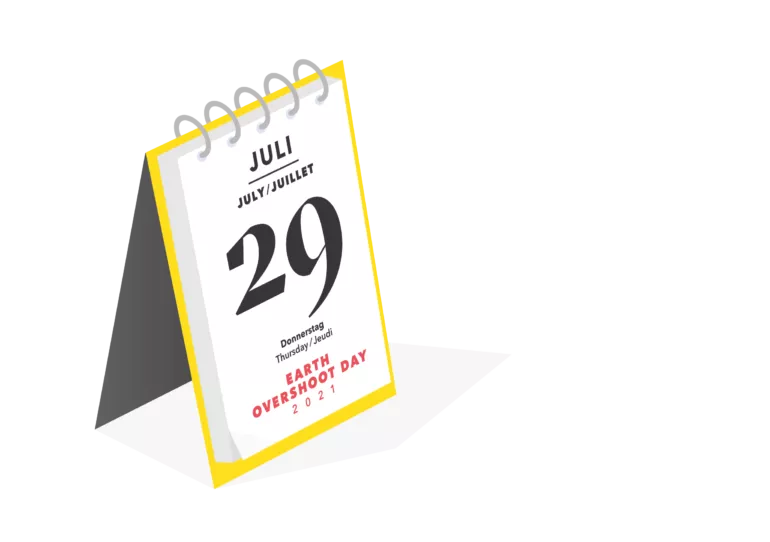

When economic output grows, living conditions improve at the same time, that was the assumption in the past and today. But the price we are paying for this is still a minor issue for many. The British economist Tim Jackson is convinced: “In pursuit of the good life today, we are systematically eroding the basis for well-being tomorrow.” Economic growth continues to build on the unstable foundation of limited resources. Every year, the intangible Earth Overshoot Day memorial reminds us that we are close to irreparably damaging our planet.

Is the time ripe to open a new chapter in economics?

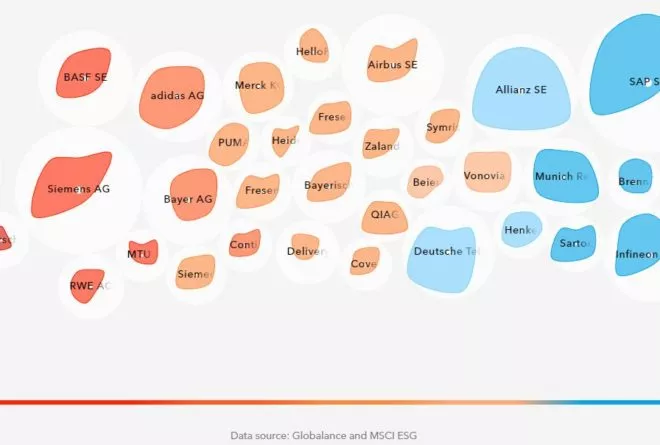

Last year, all the natural resources that the Earth can regenerate within a year had already been used up by 29 July. And can we really equate growth with widespread prosperity if there were still 811 million people worldwide suffering from hunger and two billion from malnutrition in 2020? Overall, one in ten people did not have enough to eat, while in the same year 1.1 percent of the world’s population owned 45.8 percent of the world’s wealth. Is the time ripe to open a new chapter in economics? Do we need a new economy that pays more attention to people and ecology?

Do we need an economic system which nature is embedded into?

Has the GDP Had Its Day?

Today, a company with the mantra “Business as usual” and “We’ve always done it this way” would quickly be out of date. But the ultimate benchmark for economic performance in a national economy is still allowed to pursue this strategic approach. Isn’t the GDP a bit out of fashion? Gross domestic product may have made sense for the longest time, but nowadays the negative external factors should also be taken into account. Carbon emissions, environmental pollution, health care, quality of life and social aspects are still ignored. If the farmer uses extra fertiliser to achieve a bigger harvest, economic output increases. The impact of phosphorus on groundwater is not taken into account. However, every flight, every gram of meat sold or the cleaning service after an oil spill is still counted. With regard to climate change, finite resources and social inequality, it is highly questionable whether growth alone can be the indicator of quality of life and well-being.

A Compass for the Future?

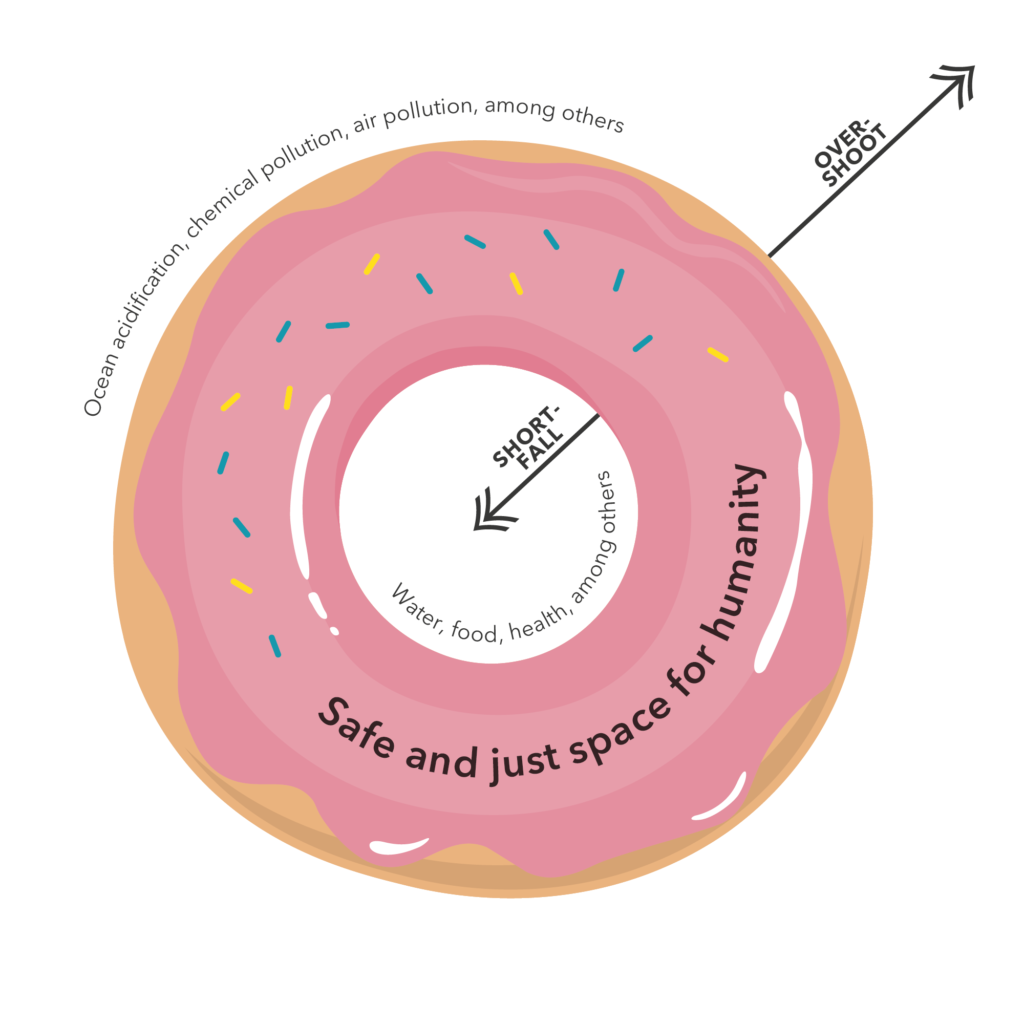

Doughnut Economics – a Well-Rounded Concept

Today, when we flip through magazines, we read about minimalism and conscious abstention, we can attend mindfulness seminars, and on Netflix, tidying experts teach us how to get rid of superfluous stuff. Has the definition of social prosperity already changed and are we heading towards a new, more conscious consumer culture? Presumably, as the so-called “Doughnut” theory by British economist Kate Raworth has met with great interest in many places. It is not without reason that her book “Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist” has been translated into 20 languages and is being used by cities all over the world. Kate Raworth wants to move away from constant maximising behaviour and instead aim for economic growth that embraces people’s real needs.

Inside the doughnut, a minimum boundary is drawn and the social foundation is laid, among other things. Hunger and poverty must be prevented, and access to health care and decent education should be guaranteed. In short: a safe, just and humane living space.

The outer edge represents Earth’s limited resource capacities, which should restrict our ecological actions to a healthy level. The doughnut also symbolises the balance of politics, economy and ecology.

Quite a few people see doughnut economics as a “compass for the future”. This is why Kate Raworth offers advice to help anyone interested understand the possibilities for transforming our economies with the “Doughnut Economics Action Lab”.

Say goodbye to maximising behaviour: strive for economic growth that encompasses people’s real needs.

Doughnuts Made in Amsterdam

In the middle of the coronavirus crisis, the Dutch city built on canals announced that it is looking into the doughnut model as it is striving for a social circular economy. Recycle, repair and share: that’s the future motto. There is an increased focus on recycling instead of new production. Amsterdam is concentrating on food, organic waste, consumer goods as well as the construction sector. For example, new construction for the public infrastructure will be circularised from 2023 and this will also apply to renovations from 2025. Bio-based building materials are already being used today. The consumption of primary raw materials is to be halved by 2030 and completely banned from Amsterdam by 2050. The goal: “a city without waste”, breaking dependence on global supply chains and creating new jobs. Not only Amsterdam was inspired by the doughnut theory, but Philadelphia, Portland and Brussels are also working together with the “Doughnut Economics Action Lab” (DEAL) think tank’s city concept.

The environment needs price tags.

Homo Economicus vs. Homo Doughnut

The concept may not be to everyone’s taste. There is too much concern about “zero growth”, which in the eyes of many economists is not an option in today’s economy. Without growth, they see the first domino of corporate losses falling, which could shake jobs and the welfare state. A transition to a new economic order is associated with many risks – even the advocates of unconventional models know this. This does not imply, however, that the current system of maximum growth must be regarded as having no alternative.

But in the end almost everyone agrees on one thing: the environment needs price tags. From a consumption tax to incentive taxes to caps on emissions, a number of proposals have been thrown into the ring – which recently also included a doughnut.