News & Trends

Is Nature Becoming a “Person”?

Why the Environment Also Has a Right to Rights

Scientists’ warnings are getting louder and louder – the loss of biodiversity is too huge. Humans have exploited natural resources for too long. And still oceans, forests, soils and ecosystems are considered mere objects in most jurisdictions. But what if we gave nature a legal voice?

Humans see themselves as the centre of worldly reality, although they only make up 0.01 percent of the Earth’s biomass. According to the UN, the unequal relationship between nature and humans and the resulting environmental damage have become the greatest threat to global security.

Focus Too Much on Humans

Today, a person can sue as a natural person and a company can sue as a legal person. What if animals, plants, landscapes and abstract environmental assets were given a subjective right and could go to court through representatives such as environmental associations or law firms? So, a polluted river could sue on its own behalf to be compensated for the restoration of its ecosystem.

We owe bees and company EUR 153 billion a year.

Indigenous Communities Show Us How

The example with the river sounds absurd. But four rivers already claimed their rights in 2017 – the Whanganui River in New Zealand, the Río Atrato in Colombia, the Ganges and the Yamuna in India. The New Zealand case is particularly exceptional as Parliament even appointed the river two legal guardians. Canada adapted this concept of legal guardianship in February 2021. The Magpie River was granted nine personal rights controlled by river stewards following two resolutions by the Innu First Nation of Ekuanitshit and the Minganie Regional County Municipality.

Indigenous communities in particular attach great importance to nature’s elements. They are often the focus of cults and rituals. So it is hardly surprising that nature as a legal subject and the indigenous expression “Pacha Mama” were incorporated into the constitution in Ecuador as early as 14 years ago. Article 72 has stated since 2008: “Pacha Mama – Mother Earth, where life is reproduced – has the right to integral respect for its existence.” A few years later, Bolivia also included the protection and preservation of the environment as a “public interest” in its constitution. It thus attributed the right to a “healthy and ecologically balanced environment” to the population.

Because of these pioneering drafts, more and more countries are having to deal with class action lawsuits from concerned and angry citizens or representatives of nature. Just recently, the Supreme Court of Pakistan prohibited the construction of new cement plants in ecologically endangered areas. The reasoning behind the judgement was based on the fact that humans and their environment must compromise for the good of both, and this peaceful coexistence demanded that environmental objects be treated as holders of legal claims.

Four rivers already claimed their rights in 2017.

Nothing Is Free

Ecosystem goods and services. This unwieldy term describes all the goods and services that nature provides without charging for them. Clean air, drinkable water, renewable raw materials, but also prevention of erosion by deep-rooted plants or all conceivable pollination activities. For the latter, we actually owe bees, bumblebees and company an incredible sum of EUR 153 billion annually – according to a calculation by the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research.

More and more political institutions are commissioning scientists to determine overall performance. This is because the last survey on the global economic benefits of all natural services refers to the year 2011. However, this figure is definitely useful for a better understanding of the “total price” of USD 125–145 trillion. The extent to which we depend on the “free” activities is shown in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report. The term “ecosystem goods and services” appears several hundred times in the 4,000-page document.

A coalition of more than 50 countries has committed to the 30×30 target to have 30 percent of the planet under conservation by 2030. Some very wealthy private individuals are now even digging deep into their pockets for this. The value of biodiversity is immense and people are starting to pay for it. Listening to nature’s voice, continuing to make it heard and also granting it rights, definitely “pays off” in any case.

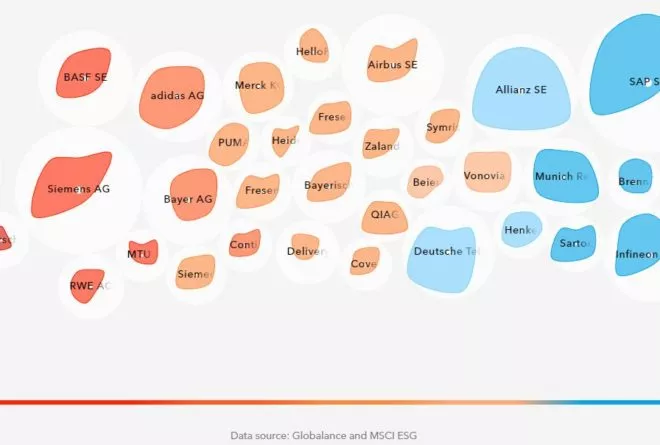

The Globalance-View

Adequate valuation of the environment is a basic principle of our Globalance Footprint® method for valuing financial assets. In our scenarios, we therefore partially correct the market’s failure that results in nature having a lack of legal personality and too low economic value. Anyone who wants to develop assets in the long term must anticipate that politics and society will demand true-cost pricing. Investing sustainably means contributing to preserving nature’s value.